Water enters the Watershed as rain or snow and leaves it in several ways. Some of it evaporates back into the atmosphere, some travels down rivers back to the Pacific ocean, some seeps into aquifers, and some is diverted and used by people. Much of the Watershed Group’s work centers on how to best manage and conserve water used by people so that streamflow and water quality also meet the needs of fish and other aquatic organisms.

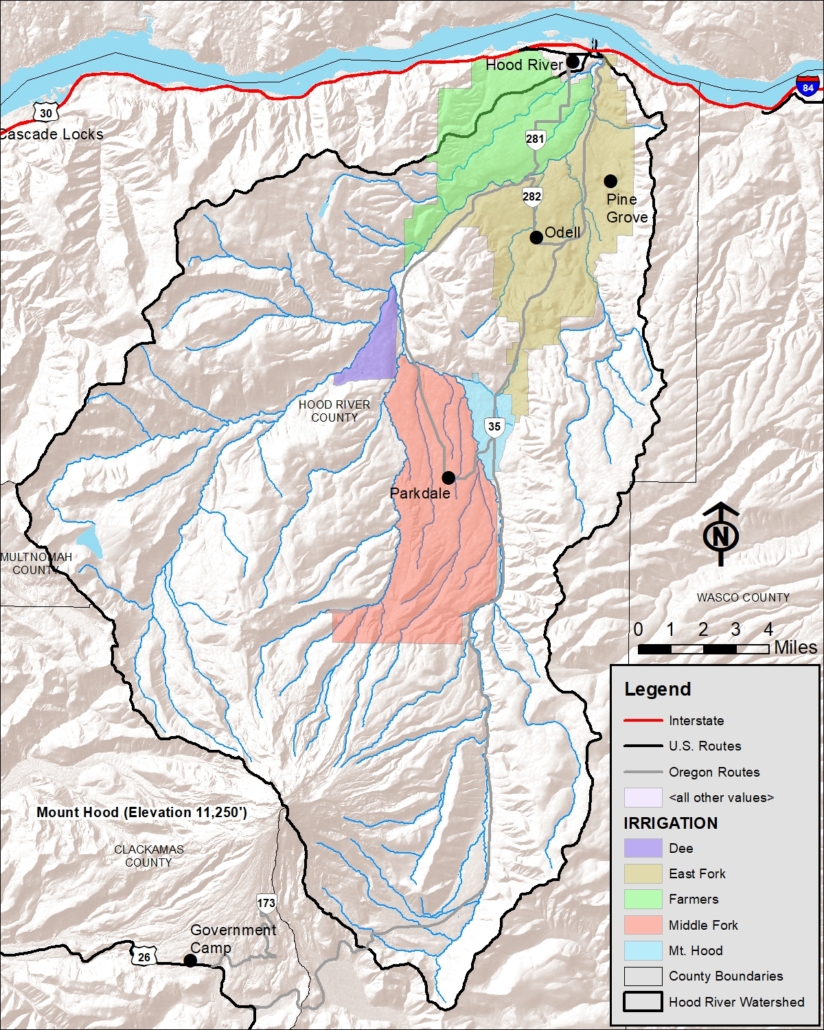

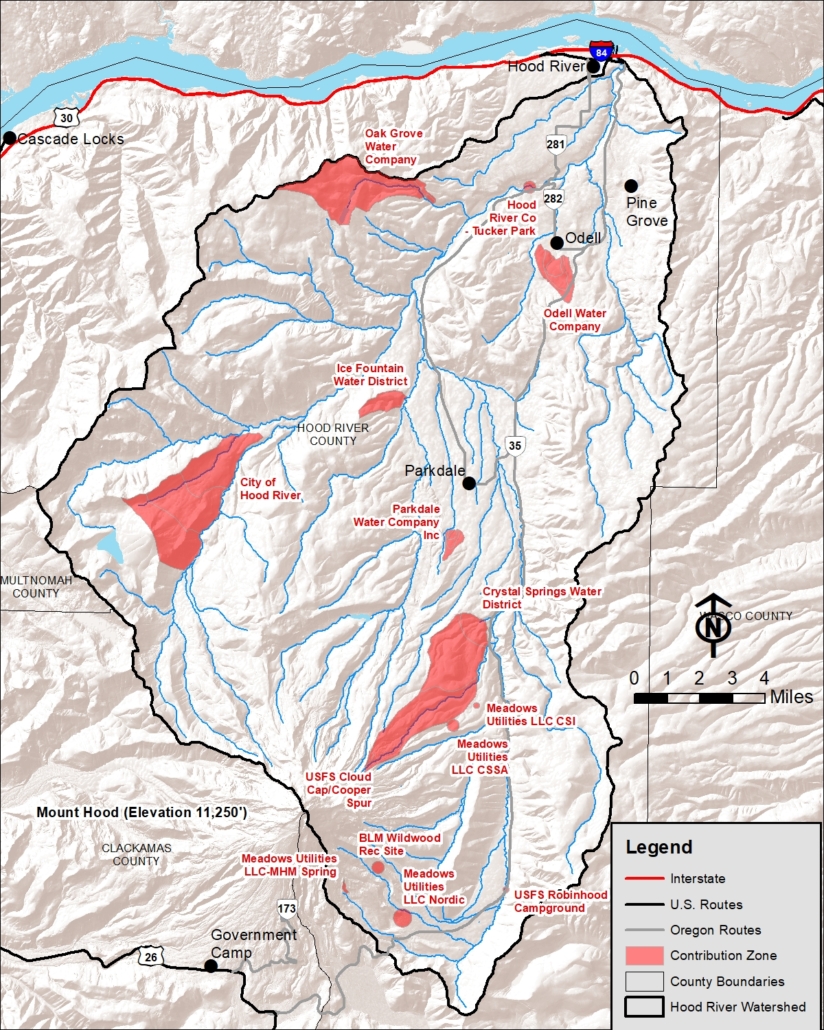

Approximately 90% of diverted water is used for agriculture. The remainder is used for domestic water (drinking, bathing, etc.), residential irrigation, commercial products (think beer and juice), and industrial processes (Hood River Basin Water Use Assessment, 2013). Most of the Watershed’s domestic potable water comes from large springs developed and maintained by the City of Hood River, Crystal Springs Water District, and Ice Fountain Water District. Water for agriculture and rural residential irrigation comes from over 15 diversions along streams and rivers, which are managed by five irrigation districts that deliver water to 23,950 acres. Middle Fork and Farmers Irrigation Districts also store surface water in Laurance Lake and Kingsley Reservoir, respectively, to augment their irrigation water in the summer. Both of these districts also operate hydropower plants that generate power from irrigation water on its way to orchards and other irrigated land. Historically, the Watershed’s irrigation districts conveyed water through open ditches and canals. While many of these have been converted to pipelines, some open canals remain, which results in significant water loss from endspills or overflows.

Mt. Hood’s snowpack and glaciers are natural reservoirs, releasing water gradually through the spring and summer. The depth of winter snowpack is an important factor in water availability during the summer months when demand for irrigation water peaks. Unfortunately, average snowpack depth has been decreasing over time and the glaciers on Mt. Hood are receding. During drier years, low streamflow reduces the quantity and quality of fish habitat and may also reduce the availability of irrigation water.

The good news is that there is a lot of opportunity to conserve water. The Hood River Basin Study, which included a Water Use Assessment and a Water Conservation Assessment, and informed the Hood River Basin Water Conservation Strategy, showed that agricultural water conservation can offset the anticipated effects of climate change on streamflow, which will protect both fish and farms in the future. The Watershed Group’s “Watershed 2040” Strategic Action Plan (coming soon) describes the strategies and projects that are planned for the next 20 years to meet this water conservation objective. This includes piping all remaining open canals and converting almost all agricultural lands to efficient irrigation technology. The Watershed Group also plans to provide information to residential landowners interested in water conservation, and work with businesses interested in technology and management systems to conserve water use in commercial and industrial operations.

Irrigation District Boundaries

Water Provider Boundaries