Fish in the Hood River Watershed

The Hood River Watershed has one of the most diverse assemblages of anadromous and resident fish species in the State of Oregon. Native anadromous fish in the Hood River Watershed include: spring and fall Chinook, winter and summer steelhead, coho, Pacific lamprey, and sea run cutthroat trout. Resident, native fish include cutthroat trout, bull trout, rainbow trout, mountain whitefish, large scale sucker, and two species of sculpin. Resident fish remain within the freshwater system their entire lives, while anadromous fish are born in freshwater, spend some period of their life in the ocean, and return to freshwater to spawn.

The Watershed’s high fish species diversity is mainly due to the fact that it straddles the transition zone between fish populations that reside either west or east of the Cascades. For example, the Watershed has both summer and winter steelhead, whereas most basins have one or the other. Finally, its glacier-fed streams provide very cold water, which supports a population of bull trout.

The abundance and distribution of fish species in the Hood River Watershed were greater historically than today. Native Hood River spring Chinook became extinct in the early 1970s, along with native coho and fall Chinook stocks. Bull trout were listed as threatened throughout their range in 1998 under the federal Endangered Species Act. In addition, steelhead, Chinook, and coho were listed as threatened in 1998, 1999, and 2005, respectively. Pacific lamprey were excluded from most of the Watershed by the Powerdale Dam, which was constructed in 1923 four miles upstream from the mouth of the Hood River. Since its removal in 2010, Pacific lamprey are re-colonizing the Watershed.

Low summer streamflow, poor habitat quality, and sediment load are the primary factors that currently limit successful spawning and production of juvenile steelhead, salmon, and other fish in the Hood River Watershed. There are also factors outside of the Watershed, such as ocean conditions and dams on the Columbia River, that limit the number of returning salmon. The Watershed Group focuses on actions that increase spawning and juvenile rearing habitat, which leads to more juvenile steelhead and salmon migrating to the ocean and ultimately returning to the Hood River to spawn.

Hood River Watershed Group partners are working to restore native fish runs in the Watershed through streamflow restoration, instream habitat enhancement, water quality improvements, and other efforts.

Anadromous fish are ecologically and culturally significant in the Hood River Watershed. Spawned out salmon carcasses provide an important food source for fish and wildlife. Larval lamprey are a rich food source for juvenile salmonids and also improve water quality by filter feeding organic material. Adult Pacific lamprey are an important traditional food and have religious, medicinal, and ceremonial importance to members of the Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs. Spring Chinook are an especially significant species in Northwest tribal culture in part because it is the first salmon to return each year and it appears as a bright, plump fish months prior to spawning.

The Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Reservation (CTWS) hold federally-reserved fishing rights in the Columbia River and the Hood River Watershed. These rights were protected as part of the Treaty with the Tribes of Middle Oregon signed June 25, 1855. The CTWS is the legal successor to signatories of the 1855 Treaty, under which seven bands of Wasco and Sahaptin speaking Indians ceded ownership of ten million acres of tribal land, including the Hood River Watershed, to the United States (BPA 1996). In exchange for these lands, the Treaty reserved to the Tribes an exclusive right to fish within Indian reservation boundaries and the right to fish in common with other citizens at all other usual and accustomed places including ceded lands.

Treaty fishing opportunity has become severely restricted because of low abundance and the need to protect weak or threatened stocks. A joint state (Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife) and tribal effort to rebuild native summer and winter-run steelhead, and reintroduce spring Chinook with Deschutes stock began in 1991. This is part of an ongoing fish recovery effort called the Hood River Production Program and is funded by Bonneville Power Administration. As co-managers, the CTWS is actively involved in habitat protection, restoration, fisheries enforcement, enhancement, and research activities.

Key Anadromous Fish Species in the Watershed

Spring Chinook |

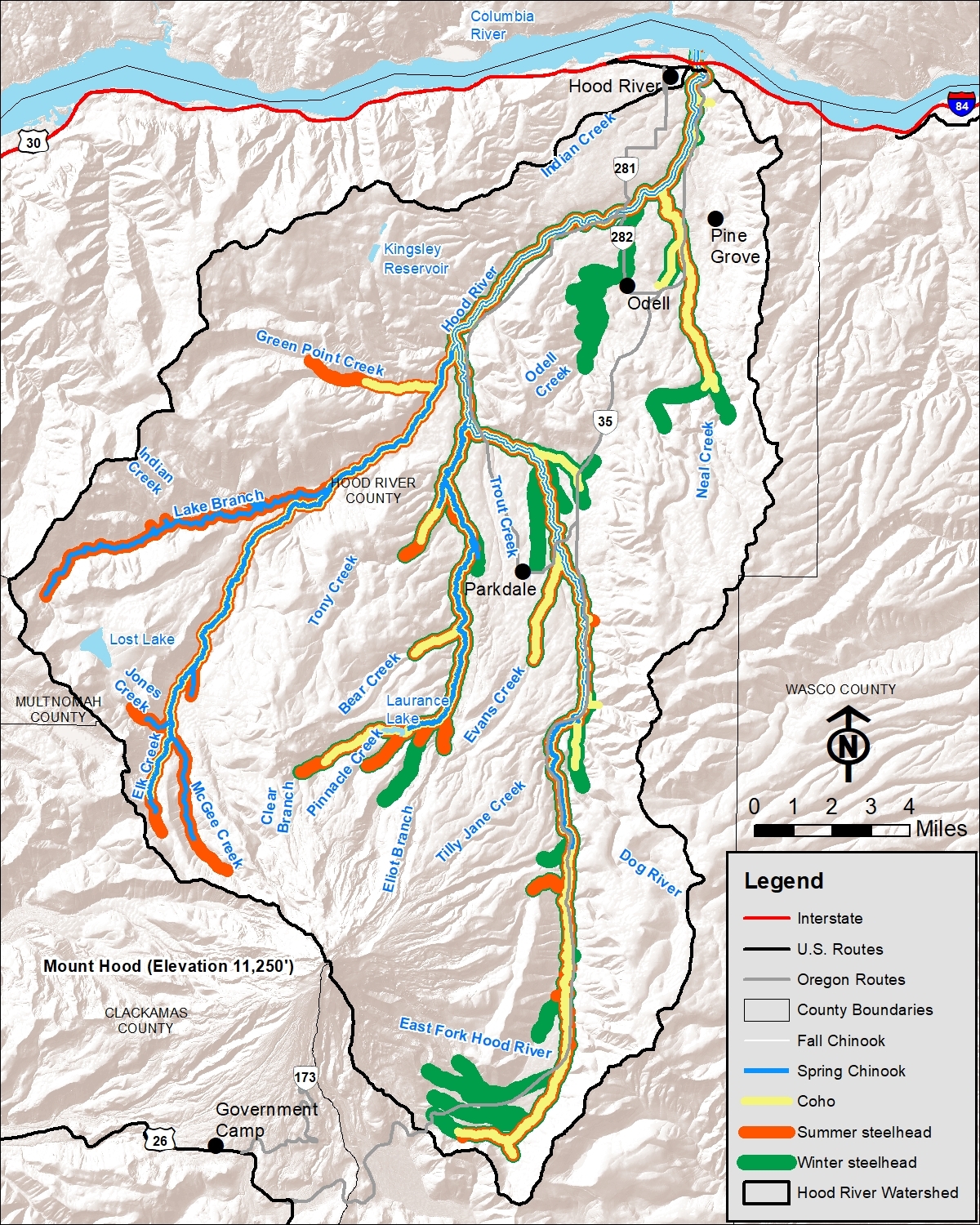

| Adults return to fresh water in the spring (generally March-May) and then spend the summer in freshwater before spawning in the fall (generally August-September). Spring Chinook tend to spawn higher in the Watershed. While found throughout the Hood River Basin, the population mostly spawns in the West Fork Hood River and its tributaries. The spring Chinook run in the Hood River Watershed went extinct around 1970. CTWS and ODFW have been working to re-establish this run since the early 1990s. |

Fall Chinook |

| Adults return to fresh water in the fall (generally July-October) and spawn fairly soon after arriving at their native stream (October-January). This run tends to spawn lower in the Watershed, especially in the mainstem Hood River. |

Winter Steelhead |

| Adults return to fresh water in the winter (generally December-May), with the majority returning to the Hood River between February-May. They spawn in the spring shortly after returning to their native stream (generally February-June). Winter steelhead are most likely to be found in the mainstem Hood River, East Fork Hood River, and Middle Fork Hood River. |

Summer Steelhead |

| Adults return to fresh water in the summer (generally March-November), with the majority arriving in the Hood River between August-October. They will spend the winter (sometimes up to a full year) in freshwater and spawn in the spring (February-April). Summer steelhead tend to spawn in the West Fork Hood River. |

Coho |

| Adults return to fresh water in the fall (generally July-November) and spawn shortly after return (generally October-February). They have been observed widely in the basin, but are most likely to spawn in the mainstem Hood River and lower tributaries such as Neal Creek. |

Pacific Lamprey |

| Adults return to fresh water in the summer and remain for up to a year before spawning. Since removal of the Powerdale Dam in 2010 they have been found several miles up the East Fork Hood River and as far as Punchbowl Falls on the West Fork Hood River. (Note: Pacific lamprey distribution not shown on map.) |

Significant Fish & Wildlife Species in the Hood River Watershed

Hundreds of species are present or potentially present in the Hood River Watershed. The species noted below are a few of the many species with particular ecological importance to the Watershed.

Beaver create and maintain wetlands and complex stream habitats of great value to several salmonid species especially as critical overwintering habitat. Beaver ponds provide habitat for wildlife species and promote stream-floodplain interaction and groundwater recharge.

American marten are a Forest Service Management Indicator species with a role as a medium home-range carnivore in mixed-conifer cover types from mid to high elevation.

Black-tailed deer and elk are managed game species and a Forest Service Management Indicator Species. Big-game movement patterns indicate the degree of connectivity across cover types in the Watershed, and are dependent upon adequate summer and winter range habitat. Grazing, browsing, and foraging by deer and elk in the Watershed influences forest vegetation structure, composition, and density.

Clark’s nutcracker is an alpine species associated with old-growth white-bark pine and is dependent on its pine cone seeds. These pines grow at high elevations at or above the timberline in the Mt Hood and Cooper Spur area. There are declines in white-bark pine stands, especially in early succession, from fire suppression, replacement by competing conifers, lack of regenerating young trees, and disease. The pine appears to be totally dependent on Clark’s nutcrackers (Marshall et al. 2003) for stand regeneration. Clark’s nutcrackers cache huge numbers of white-bark pine seeds (up to 100,000 seeds per bird each year) in small, widely scattered caches usually on bare ground. This is ideal for regeneration of the pine since many caches are never used.

Lark sparrow is associated with oak savanna, oak-pine stands, and eastside interior grasslands found mostly along the mid to lower eastern boundary of the Hood River Watershed. Western gray squirrel is an Oregon Game Species and a Forest Service Management Indicator Species, that uses a Ponderosa pine dominant, westside oak and dry Douglas-fir forest type. Fire is an integral part of the ecosystem for both the lark sparrow and the western gray squirrel and helps control invasive plant species and retain native plant species.

Northern spotted owl is associated with mixed-conifer forest cover types with old-growth or late-succession forest structural characteristics (snags, coarse woody debris, and multiple vegetative layers). Large contiguous blocks of forest are critical to the owl’s successful reproduction and survival.

The tables below list fish and wildlife species that are known to occur in the Hood River Watershed that have federal or state protected status, or are recognized as rare or ecologically significant. Learn more about these species and efforts to protect and recover them in the Oregon Conservation Strategy.