We all live in a watershed.

If you live in Parkdale, the City of Hood River, Odell, Mt. Hood, Dee or somewhere in-between, then you live in the Hood River Watershed.

If you have skied Heather Canyon, camped at Lost Lake, biked the trails at Family Man, or hiked to Cooper Spur, then you have played in the Hood River Watershed.

If you have eaten a pear from Parkdale or blueberries from Dee Flat, drank coffee in the Heights, or beer or cider from one of the breweries between Hood River and Parkdale, then you have consumed the water of the Hood River Watershed.

A watershed is the land area that drains to a particular lake, stream, or river.

OUR WATERSHED

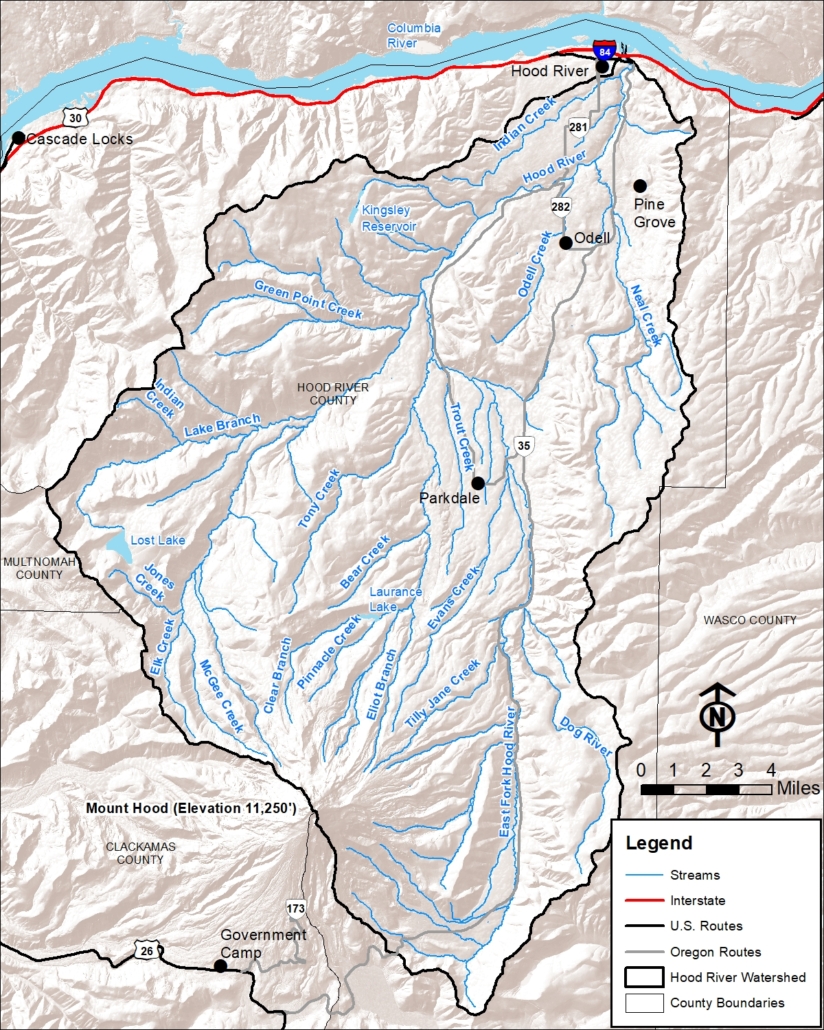

The Hood River Watershed is defined as the area in which all water runoff ultimately drains into the Hood River above its confluence with the Columbia River. This 339-square mile watershed originates on the eastern side of the Cascade Range in Oregon. Its rivers flow north from the 11,245 foot peak of Mt. Hood to the Columbia River at an elevation of 74 feet, 22 miles upstream from the Bonneville Dam. As watersheds go, it is compact and steep, and its hydrologic response is fast. The Watershed’s great topographic relief is reflected in steep gradient streams with coarse streambed material and glacially-derived, silt-laden water. The headwaters drain into three main tributaries, the East, Middle, and West Forks of the Hood River, which converge to form the Hood River main stem about 12 miles upstream from its confluence with the Columbia River.

The geology of the Hood River Watershed is also diverse because it is at the transition zone between the Columbia Plateau and High Cascades geologic provinces. The underlying bedrock is mostly Columbia River Basalt more than five million years old, topped by layers of younger lava flows from centuries of eruptions on Mt. Hood and smaller volcanoes scattered across the Watershed (USGS Volcano Hazards Program). Shallower layers of rock, sand, and silt come from numerous Mt. Hood lahars and debris flows, as well as from the colossal Pleistocene-era Missoula floods that descended the Columbia River Valley more than 10,000 years ago. Pleistocene-era glaciers carved steep narrow valleys into the basalt and layers of sediment on the flanks of Mt. Hood, and remnants of these glaciers are present at elevations above 6,000 feet on Mt. Hood today. Runoff from melting of these glaciers and adjacent snowfields provides a major source of irrigation and domestic water in the Hood River Watershed. Learn more about the geology of the Hood River Valley by checking out this Dogami map.

The Hood River Watershed

RIVERS & STREAMS

Five Hood River tributaries are fed by glaciers on Mt. Hood, including Newton and Clark Creeks in the East Fork, Coe and Eliot Branch in the Middle Fork, and Ladd Creek in the West Fork. As these glaciers melt and recede during the summer, fine sediment is exposed and carried into the streams, giving them a greenish milky look from the “glacial flour”. During the winter, heavy rain events increase streamflow, which can move large amounts of sediment, gravels, cobbles, and boulders downstream. A dramatic example of this process occurred in 2006 when a massive debris flow originating at the base of Elliot Glacier tore through the Middle Fork of the Hood River into the mainstem. The debris flow deposited acres of wood, sand, and rocks at the mouth of the Hood River to form what has become known locally as the “Spit”.

Historically, downed wood and log jams were more common in the Watershed’s streams, which contributed to greater stream habitat complexity than exists today. Large trees were drawn into the stream by natural forces such as bank erosion, windfall, landslides, and floods. The resulting woody debris formed log jams and obstructions, trapped gravel, created pools and cover for fish, provided a substrate for fungi, bacteria, and invertebrates, and dampened the velocity of water flow. Alder, willow, and cottonwoods dominated gentler gradient floodplains while conifers dominated the riparian zone in higher gradient areas. Much of the lower East Fork consisted of a series of wide wetland complexes within a braided stream network where downed logs, side channels, and continuous riparian forest stands were common.

Human disturbance throughout the Hood River Watershed has compromised the river system and limited aquatic habitat productivity. Activities such as dam construction, road building, logging, irrigation and municipal water withdrawals, conversion to agriculture, and development have contributed to fish passage barriers, low instream flows, lack of habitat complexity, and impaired water quality. The Powerdale Dam, built in 1923, was a major impediment to water flow on the mainstem of the Hood River just below Neal Creek until it was removed in 2010.

Learn more about where our water comes from, Hood River Watershed forests and farms, and the people of the Hood River Watershed.

Find additional Watershed background information in the Hood River Watershed Assessment.

Find additional Watershed historical information here.

square miles between Mt. Hood and the Columbia River

main branches: the West Fork, Middle Fork, and East Fork

threatened fish “runs”: spring Chinook, fall Chinook, bull trout, winter steelhead, summer steelhead, and coho. The Watershed also contains the ESA-listed northern spotted owl.